The Island

The year was 2002. One day while talking with my Dad I asked him if there was anything special he and Mom would like to do that summer. It didn’t take long for him to tell me that it was a lifelong dream of his to go to the island in Canada that our family once owned. All he knew was the story his paternal grandmother Celestine (Derosier) Peltier had told him. The story, as recorded by my Dad, was that, “Lord D. Derosier, our great-grandfather owned the island. Queen Victoria took the throne at about 12 years old and on a trip to Canada, this had to be after Canada was won from the French, the people had to pay allegiance to the Queen. Grandma said great-grandfather would not bow down to the Queen, a young girl, and he was exiled aboard his fishing boats and died, never setting foot on English soil again. She told me there was a cloud on the title to the island.” What I took from the story, was that our family had once owned an island in Canada and Queen Victoria had taken it away. All I could think is that there must be thousands of islands in Canada. Which one? Where? Who? When? It would not be a simple dream to fulfill.

I had many more questions than I had answers. The one thing I was fairly certain of is that the story had come through my great-grandmother’s side of the family. I had not worked much on those branches of the family tree so my thought was to locate someone else that had worked on them. I posted what I knew on an internet genealogy bulletin board. After that, all I could do was to wait. About a month went by before I received a response. The woman who wrote me said that while growing up she had heard the same story from her grandfather Jean Baptiste Derosier. He was one of Celestine’s brothers. She said that she had been searching for the answer since the 1970s. The email had a 520-page file attached that contained the ancestors of Marie Celestine (Derosier) Peltier dating all the way back to the 7th century. I was told I would find the information I wanted on pages 131-133. Upon turning to those pages I found my 9th great-grandparents Louis Jolliet and Claire Francoise Bissot. It turned out that Louis Jolliet was the relative who had owned the island in Canada and that island was Ile d’Anticosti (Anticosti Island).

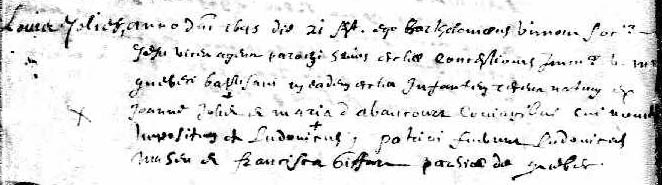

Louis Jolliet (or just Jolliet) was born to Jean Jolliet and Marie d’Abancourt on, or shortly before, September 21, 1645 in Quebec, Canada. He was baptized September 21, 1645 at Notre-Dame de Quebec, Quebec City.

Translation:

Louis Joliet

In the year of the Lord 1645, on the 21st day of September, I, Barthelemi Vimont, of the Company of Jesus, doing the duties of parish priest of this church of the Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Mary, of Quebec, baptized in the said church, a child recently born to the spouses Jean Joliet and Marie d’Abancourt, on whom the name Louis was imposed. The godfathers were Louis Maheu and Francoise Giffart, of the parish of Quebec. [I’m not sure about “godfathers” because Louis is male and Francoise is female.]

End of translation.

Louis was the 3rd of 5 children born to Jean and Marie. Only four of their 5 children survived to adulthood: Adrien, Louis, Marie and Zacherie.2

Around 1656 Jolliet entered the Jesuit College in Quebec City to study to become a priest. There he was schooled in philosophy, theology and music. During this time he became an accomplished harpsichordist and organist. By 1662 he took his minor orders and in 1666 he defended his thesis in philosophy while working as a cleric. For unknown reasons, in 1667, he left the priesthood. Under the patronage of Francois de Laval he traveled to France for a year and upon his return to Quebec he became a coureur de bois (fur-trade entrepreneur).

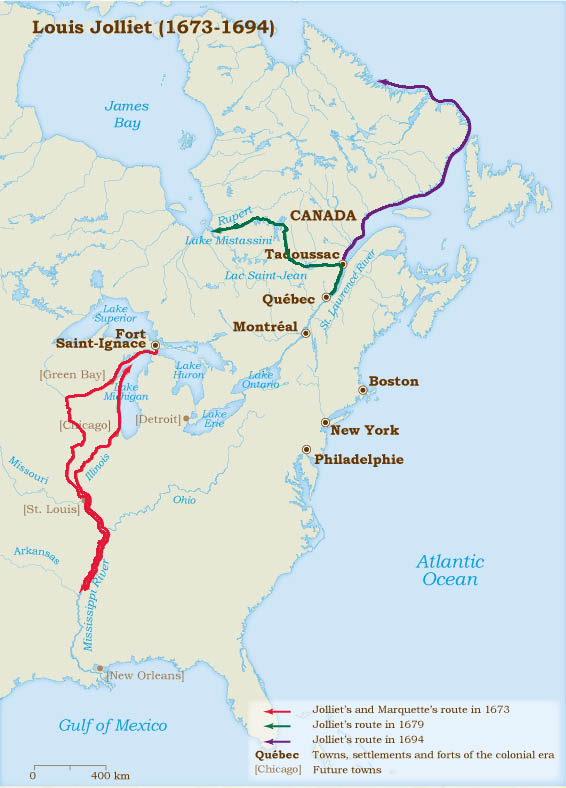

His place in history would be cemented when on May 17, 1673 he left on an expedition to determine whether the Mississippi flowed into the Gulf of Mexico or the Pacific Ocean. Jolliet was accompanied by about six others, including Jesuit Father Jacques Marquette as translator. By mid-July the group had traveled the Mississippi River south to about the mouth of the Arkansas River. The group decided to turn back when friendly Aboriginals warned them of possible hostile forces further down river. They felt they were armed with enough information to prove that the river did flow into the Gulf of Mexico and not into the Pacific Ocean. To some this would be a great disappointment as many already believed it was a passage to the China Sea. That did not diminish the fact that Jolliet was the first non-Aboriginal person, together with Jacques Marquette, to travel and map the Mississippi River.

On the trip back Jolliet spent the winter of 1673-74 at the Jesuit mission at Sainte-Marie falls [Sault Ste. Marie] making copies of his log-book and maps that he had drawn during the course of the expedition. The duplicates were left with the Jesuits. In May 1674 Jolliet embarked for Quebec with his original records. Tragedy struck about a month later at the Saint-Louis rapids. His canoe, his companions and all the contents were lost when the canoe capsized in the rapids. Jolliet was the only survivor. This loss was further compounded when sometime thereafter the mission at Sainte-Marie falls burned and the copies of his discoveries were also lost. Only what Jolliet supplied from memory is what survived this great expedition.

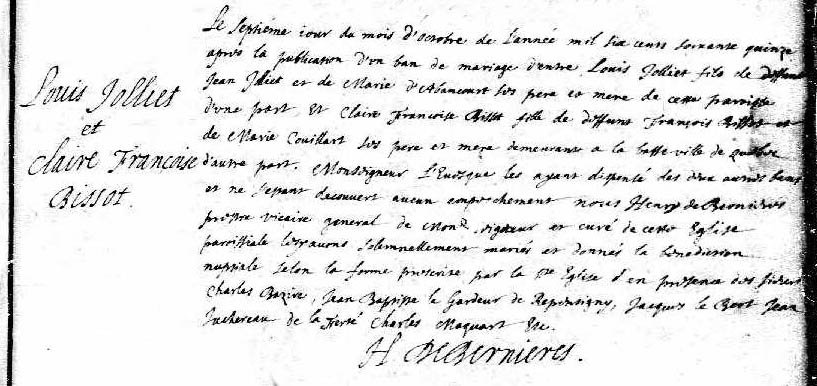

Jolliet married Claire Francoise Bissot on October 7, 1675 at Notre-Dame de Quebec in Quebec City. (Their marriage record is difficult to read so I decided to not translate it.)

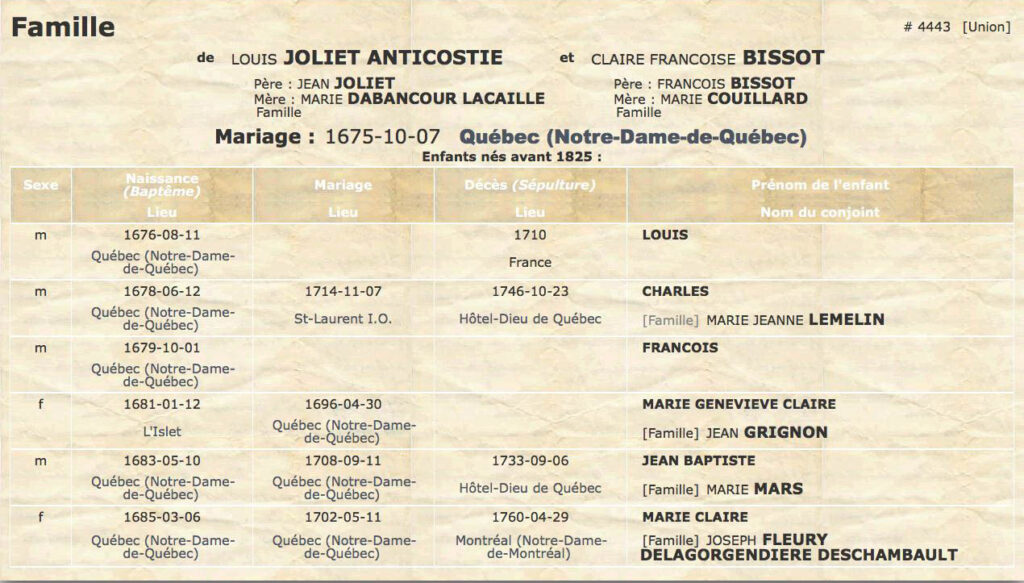

Their union produced 6 children: Louis, Charles (my 8th great-grandfather), Francois, Marie Genevieve Claire, Jean Baptiste and Marie Claire.

Jolliet returned to the fur-trading industry and in March of 1679 he became the seigneur of the Iles de Mingan (an archipelago of islands on the north side of the St. Lawrence River), and he was granted Anticosti Island in 1680.

As a skilled hydrographer, cartographer and explorer, Jolliet was commissioned in April 1679 by Quebec officials to make an overland journey to Hudson Bay to survey the influence of English traders and to assess the possibility of trade expansion with the Aboriginal people in the area. Upon his return, Jolliet recommended that the French “remove the English from this bay,” or at the very least, “prevent them from establishing themselves any further, without driving them out or breaking with them.”

In the years that followed he developed cod, seal and whale fisheries on his properties. His summers were spent with his family on Anticosti Island where, in addition to working his business operations, he built a fort maintained by soldiers. These were prosperous times and his warehouses were filled with goods. His winters were spent at his home in Quebec City.

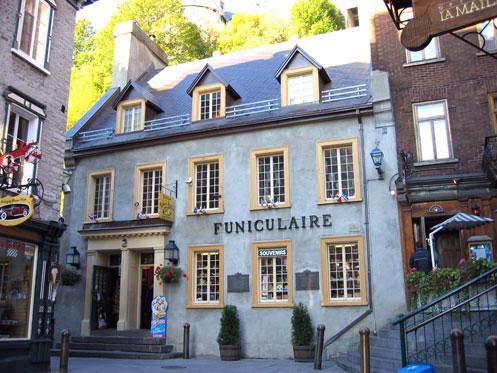

(now a gift shop and site of the lower platform of the Funicular)

Jolliet and his family were enumerated in the 1681 census on Anticosti Island. The record shows that Jolliet is 42 years old, Claire (Francoise) is 23 years old, Louis is 5, Jean 3, Anne 2 and Claire 1. The domestiques (servants) shown as residing with Jolliet’s family are: Jean 30, Pierre 25, Louise 22, Pierre 33, Georges 19 and Andre 18. Also counted in the household were 6 fusils (guns), 2 betes a cornes (horned beasts, probably oxen) and 2 arpents en valeur (metric acres of value, which is probably the amount of land they had cleared for crops).6 2 arpents is less than 1.5 football fields in size.

Sadly Jolliet’s good fortune did not last. In 1690, in the midst of the King William’s War (the North American theater of the Nine Years’ War), ships commanded by Sir William Phips sailed toward Quebec City in hope of seizing the capital of New France. In route they pillaged Jolliet’s Anticosti warehouses and took his wife and mother-in-law prisoners (they were later released). Jolliet was further ruined financially when in 1692 two English ships sacked and burned his outposts at Mingan and Anticosti.

Jolliet’s final expedition in 1694 was along the Labrador coast, which he mapped and described. The many maps he had produced over the years rendered navigation in the St. Lawrence River and gulf area safe.

In 1697 Jolliet was appointed “Royal Hydrographer,” and taught hydrography at the Jesuit College in Quebec. It is believed that he only taught during the winter months and the summer months were spent on his lands at Mignan and Anticosti.

In the spring of 1700, Jolliet left for Anticosti Island and was never seen again. He is last recorded as being present at the wedding of Jerome Corda and Anne Normand on May 4, 1700 in Quebec City. Although his body was never found, a Mass was celebrated for his soul on September 15, 1700. At that service he was recognized for “having played the organ in the Cathedral and parish for many years. Done without pay.”

As it turns out, the island had not been taken away from the family by Queen Victoria, nor did Louis Jolliet lose it as he was still the rightful owner of the island when he died. I find it amazing that the story was even partially intact after having been passed down for 10 generations. I am the 11th generation to have heard the story.

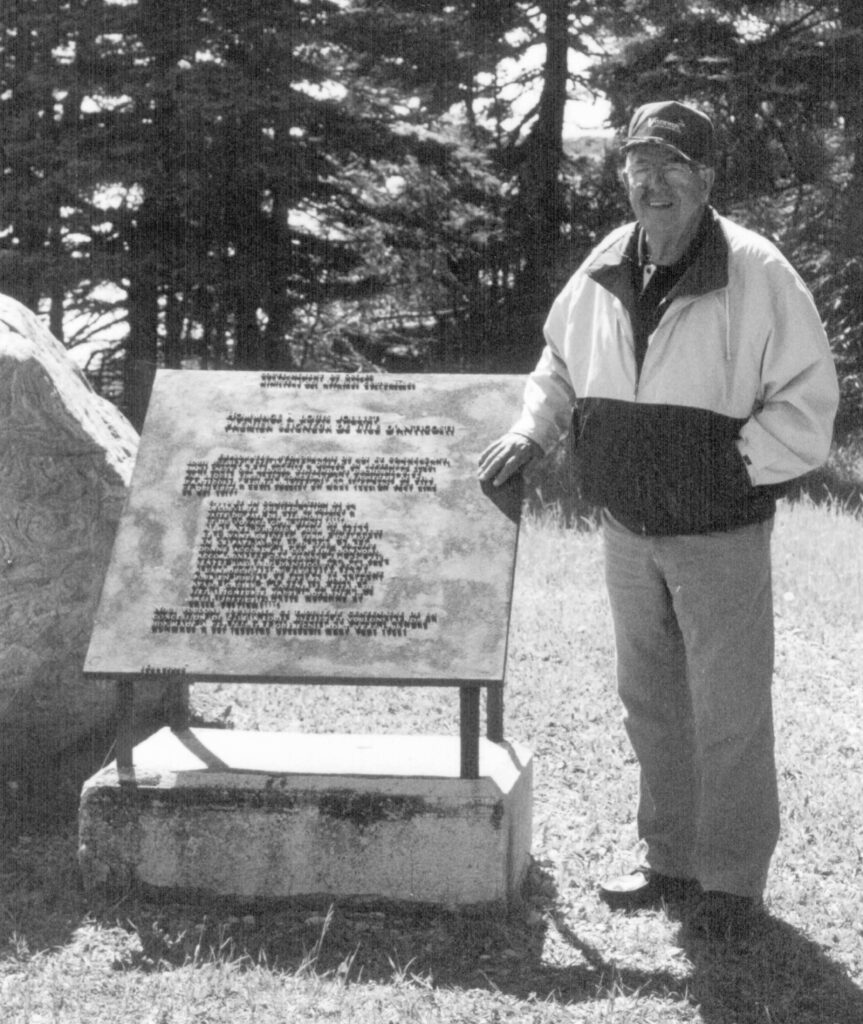

Dad, Mom and I made the trip to Anticosti Island that summer of 2002. It took us a week to drive from Minnesota to the end of the road on the north side of the St. Lawrence River and then there was a short plane ride, in a 4-seater airplane, out to the island. Every day we marveled at the scenery, toured the island and ate great food. During our stay on the island we did not encounter anyone who spoke much English. We knew that people, including our guide Julie LaVallee, wondered why we had come to Anticosti, but we were unable to convey to them that our relative Louis Jolliet once owned the island. It wasn’t until the third day of touring the island that our guide took us to the plaque honoring Louis Jolliet. Using the few French words we knew, we told her something like “Louis Jolliet famille.” We knew she understood and we also knew that she was amazed that we had traveled all that way just to visit the island our relative once owned. Dad got his wish; his dream had come true.

Louis Jolliet is only directly connected to the Peltier side of the family tree. However, his mother Marie d’Abancourt remarried after the death of Jolliet’s father, and a son from that marriage, Jolliet’s half-brother Jean, became one of my 8th great-grandfathers through both the Peltier and Vadnais sides of the family. Marie d’Abancourt was both my ninth and tenth great-grandmother. The following show the line of descendants for these 2 branches.

Thanks for visiting, come back soon,

Cindy

© 2022 Copyright by Cynthia Vadnais, All Rights Reserved