Fille du Roi, Marie Anne Richard

Marie Anne Richard was one of my 8th great-grandmothers on the Vadnais side of the family. She was the first “filles du Roi” ancestor I came across while doing family research.

Anne was born to Pierre Richard and Anne Masson February 15, 1650 in France.1 Records vary as to the location; I believe she came from somewhere around Paris.

About May 1669, seventeen King’s daughters embarked on the Pot de Beurre arriving in Quebec at the end of June. The charter contract for the ship was signed on April 6, 1669 at the notary Teuleron in La Rochelle, France. The contract between Pierre Gaigneur and Captain Frederick Booterpot, a Dutchman, was made “for and at the rate of one thousand and fifty pounds by each of the months that will be used for the said voyage, insured from now on for six months, which will be counted and begin to run on the first of May next, even earlier if the said vessel sails to go on the said voyage”. In addition, “an express clause in the event of a declaration of war between France and the States of Holland during the voyage would oblige the charterer to free the ship quits and free and to hand over to the captain the passport of France in order to return freely to his country. It is said that Captain Frederick Booterpot boarded the ship as a passenger.”2

The first mention in Quebec of Marie Anne’s future husband, my 8th great-grandfather Antoine Daunay is on June 17, 1661, when at 23 years of age he is shown as being hired at Chouart des Groseilliers in Trois Rivieres, Quebec as a farmer/ploughman contracted for 3 years.3,4 He is listed in the Catalogue des immigrants as having arrived in 1661 aboard one of four ships: le Taureau, la Marie, la Marguerite, or le Saint-Pierre. Even though he could have returned to France at the end of his contract, for some reason he chose to stay.

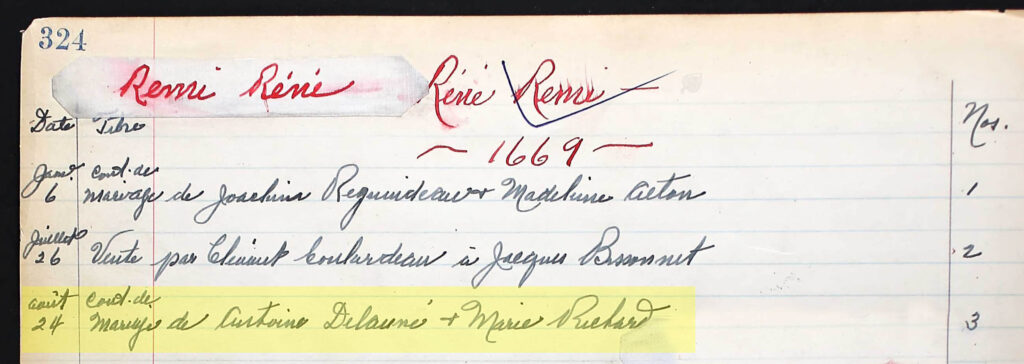

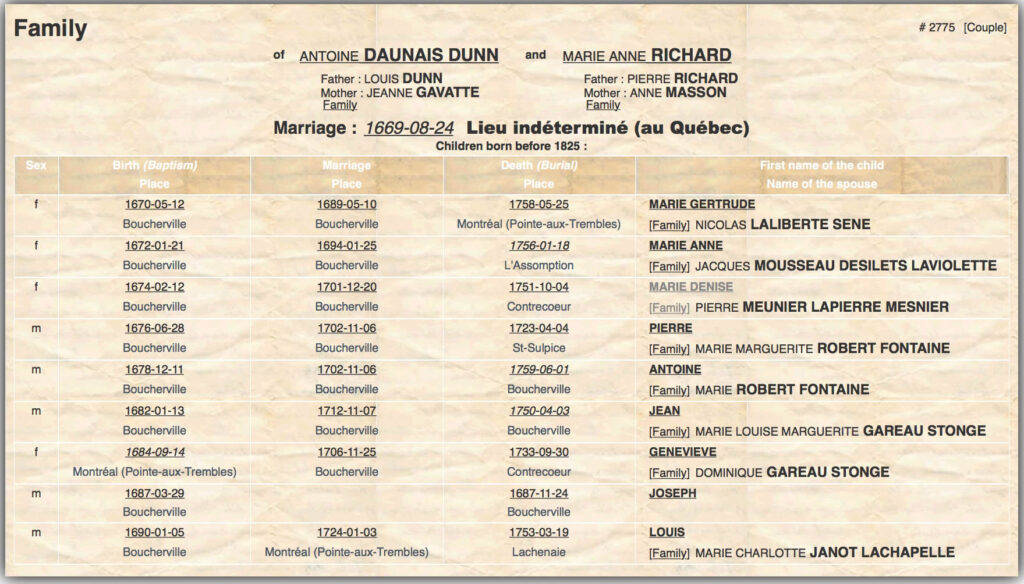

On August 24, 1669, not long after her arrival in Quebec, Marie Anne married Antoine Daunay (other spellings are: Daunet, Daunais, Dunn, Donet, Delaune, Daure, Donay). Although I have searched numerous church registers for their marriage record, the only thing I found was their marriage contract. It’s unknown exactly where in Quebec they were married.

Between 1670 and 1690 Antoine and Marie Anne had 9 children, all born in Boucherville. The second oldest, Marie Anne, married Jacques Mousseau Desilets Laviolette. They are my 7th great-grandparents.

Antoine and Marie Anne are enumerated in the 1681 census as living on Seigneurie de Boucherville of which Pierre Boucher is the seigneur. Antoine is 40 years old and Marie Anne is 34 years old. The children listed are Marie 11, Anne 10, Denise 8, Pierre 5, and Antoine 3. They own 1 vache (cow) and 7 arpents (metric acres) of value.7 Seven arpents is the equivalent of about 4.5 football fields.

The 1681 census for all of Quebec shows that the total counts were: 9,710 persons of all ages and all sexes; 1,810 guns; 6,936 horned beasts (probably oxen); 78 horses; 16 donkeys; 600 sheep; 18 goats; and 24,427 arpents of land in value.8

Also given in the 1681 census is the fact that Antoine and Marie Anne’s farm was a part of a seigneurie. “Based on the European feudal system, seigneuries were plots of land given to noblemen – who were called seigneurs – in return for loyalty to the King and a promise to perform military service when necessary. The seigneur also had to clear land and encourage settlement within a certain amount of time. The seigneur sublet his land in smaller parcels to peasant farmers. Both seigneur and tenant had obligations to each other. The tenant farmer was obliged to pay a nominal rent for the land and give one-fourteenth of his grain harvest to the seigneur. The seigneur was obliged to build and maintain a mill for grinding the grain. He was also responsible for settling disputes and acting as local magistrate upholding French civil law.

The seigneurial system worked against economic development in the colony. The dues imposed on the peasants were potentially quite heavy and had the effect of stopping the peasants from accumulating any surplus which they could use to start new enterprises. The seigneurs, who had money, tended to spend it outside the colony on goods from France rather than put it into the economy of the colony.

Unlike the serfs of feudal Europe, however, the tenant farmer or habitant was not tied to the land. He could move to a different piece of land by selling one lease and buying another.”9

It was a humble lifestyle. In the book A Short History of Quebec, the authors wrote that, “During the seventeenth century, home interiors were austere, and often smoky. The main furnishings consisted of a large curtained bed for the parents, a chest, a table and benches, cooking utensils, and straw mattresses for the children. In summer, houses were infested by mosquitoes and flies; in winter, family activity centred (sic) around an open fireplace.”10 In the community the hub of any social life would be centered on the church; the settlers of Quebec were deeply religious. The environment was not only foreign, but often hostile. More so than attacks from animals, they were in danger of attacks by unfriendly Indigenous people. For example, the task of clearing land generally involved 2 people: one cleared the land while the other, armed with a gun, stood guard.

Everyday life for Antoine and Marie Anne would have involved a lot of hard work. Farmers, although poor by some standards, usually lived better than many of their counterparts back in France. In order to supplement the family income it was not uncommon for the father to become a coureur de bois (fur trader) as the children grew and were able to take over the chores on the farm.

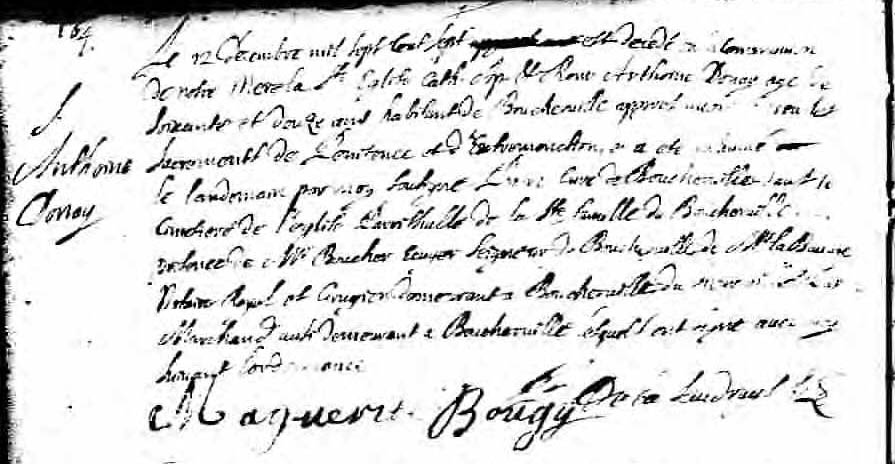

Both Antoine and Marie Anne passed away in Boucherville. Antoine died December 12, 1707 at age 72 and Marie Anne died March 19, 1713 at age 70.

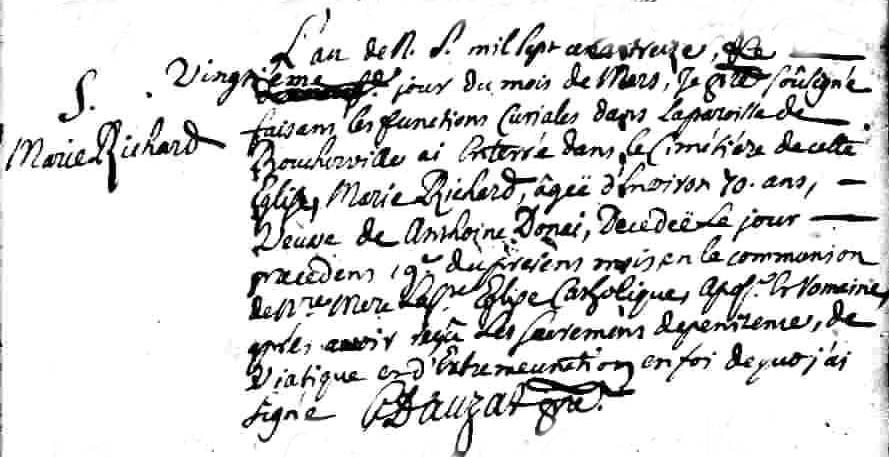

(I cannot read the record, so sorry, no translation.)

Translation:

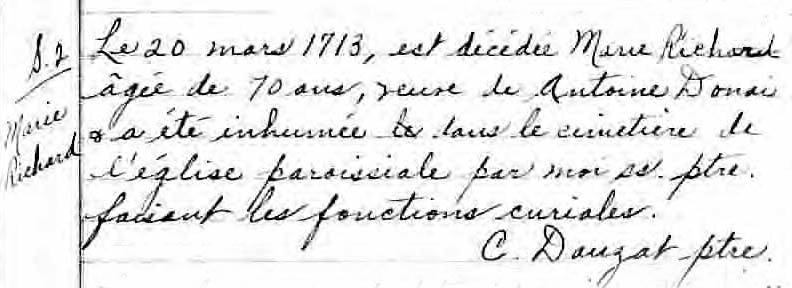

Sepulture 2

Marie Richard

On March 20, 1713, the deceased Marie Richard aged 70, widow of Antoine Donais was buried in the cemetery of the parish church by me, the undersigned priest doing the curial functions.

C. Dauzat, priest

End of translation.

The above is the original burial record for Marie Richard. Seven lines down in the record is, “19 du presens mois” telling us that she died on the 19th of the present month (March). The preceding rewritten burial record did not contain this important information.

Thanks for visiting, come back soon,

Cindy

© 2022 Copyright by Cynthia Vadnais, All Rights Reserved

Footnotes for Fille du Roi, Marie Anne Richard post

Fille du Roi, Marie Anne Richard Read More »