Mercy Adams, also known as Marie Ursule, my 7th great-grandmother, was born to Charles and Rebecca (Smith) Adams on March 13, 1674 at Oyster River, Durham, Stafford County, New Hampshire. I will use 1674 as her birth year, even though I believe she was born several years later. Her father Charles was born in England and her mother Rebecca, like Mercy, was born at Oyster River. When Mercy was born, Charles was in his early 50s and Rebecca was around 30 years old. Mercy, unlike the vast majority of my other paternal relatives, was born into an early American Protestant family.

Mercy was around 14 years old when King William’s War (1688-1697) began; referred to as the Nine Years War in Europe and the Second Indian War in North America. It would be the first of six colonial wars pitting the French against the British. As with most wars, the reasons for the war are simple: a desire for more power, more land and more money. During the war there were numerous raids perpetrated by both sides, with retaliations that followed. Some Native populations had no choice but to be involved because of promises made and broken, along with their way of life and very existence being threatened.

Much of written history favors the person or group writing that history. What has been written about the Indigenous people of North America is often one-sided, with the Natives as the aggressor. Of all of the history I’ve read about the Raid on Oyster River (generally it’s labeled as the Oyster River Massacre) I think that the most probable story is as follows:

“To understand why the Raid on Oyster River occurred, we must look into the motivation behind such an attack. In this case, the anger and frustration came from the Treaty of Pemaquid. Though the colonists and Native Americans once had peaceful relations, as time went on, the colonists began to invade more and more of Abenaki territory. The British settlers began to morph the land to fit their own needs, which was a drastic change from the Abenaki’s way of life which revolved around the land, not making the land revolve around themselves.

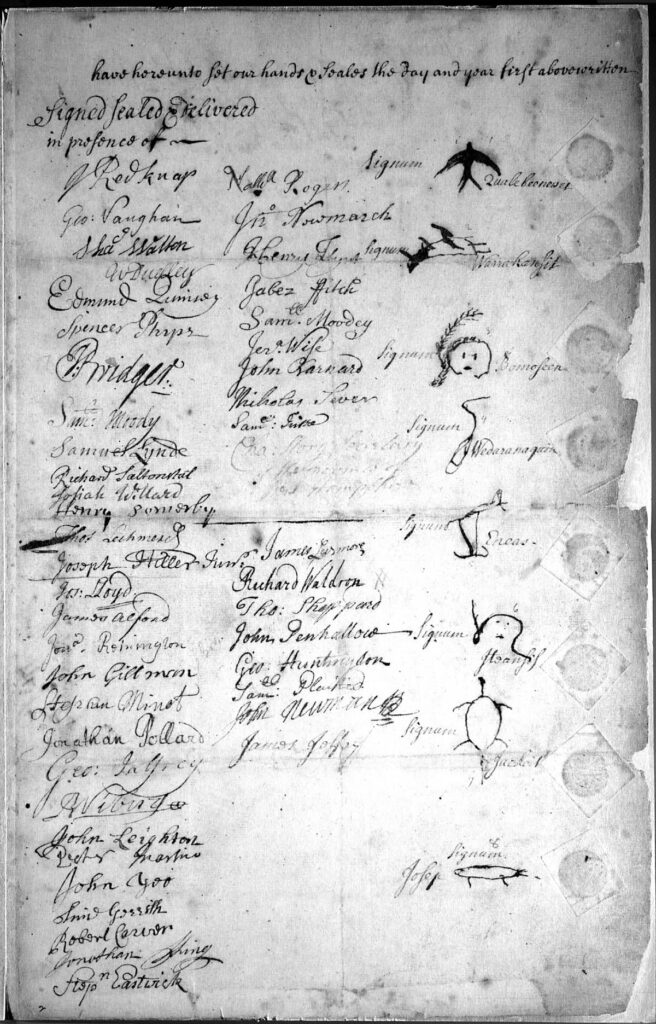

The Abenaki soon realized that they needed to take action to save their land, people, and culture. Therefore, they made an alliance with the British’s enemy: the French. The Abenaki did not want to go to war, they simply wanted to recover their people who were stolen and take back the land that they rightfully owned. As European customs became more familiar to the Abenaki, they began to become involved in treaties and compromises. Most of these treaties were disregarded and broken by the colonists who wanted more land.The Treaty of Pemaquid was signed in 1693, one year before the attack on the Oyster River Plantation, and its terms outlined “peace and trade conditions between the British and Abenaki.” There were 13 Abenaki chiefs who signed the document, and the colonists took this as a generalized agreement from all Indigenous communities, but their error “reflected a dangerous lack of understanding of Indian politics and social structure.”

In Abenaki culture, every tribe had a chief, meaning only the 13 tribes whose leaders signed the treaty had made a compromise with the British. Any tribes whose chief did not sign the treaty held no obligation to adhere to the compromises made with the British, and so they continued their alliances with the French. Those that did sign the treaty did it for the protection of their people.

When the governor of New France, Louis de Bade Frontenac, heard about the signing of the Treaty of Pemaquid, he realized he needed to keep the other Abenaki allies on good terms if the French were to win the war. Frontenac created a raid group, consisting of French military and Abenaki allies, to invade Oyster River Plantation. The group was led by the French officer Claude-Sebastian de Villieu and the Abenaki Cheif (sic) Bomoseen.

The true target all along was the Oyster River Plantation, not Boston, because the Abenaki wanted to free some of their prisoners and retaliate against the English for breaking their promises. It was known that the Abenaki were not following Villieu, but rather they were following Bomoseen. When Villieu wanted to change plans or go a different way, the Abenaki stuck to their original plans and kept marching toward the Oyster River Plantation.”2

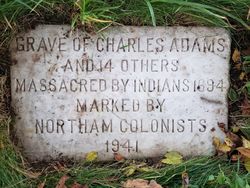

The raid on Oyster River, a frontier village of 12 garrisoned houses and a number of unprotected homes, occurred on July 18, 1694 when Mercy was about 20 years old. That morning about 250 Abenaki warriors raided the stretch of houses and garrisons located along some 6 miles on either side of the Oyster River. According to accounts, “They gained entry to the house [Adams garrison] undetected. In an instant, the warriors set upon the sleeping family. Within minutes, Charles Adams and fourteen members of his household had been tomahawked in their beds. The only survivor was a daughter named Mercy. Her captors carried her to Canada, where she remained for the rest of her life.”3

As was the custom, the priest that accompanied the group of raiders made his way to the meeting house where he remained to protect it from damage. After the raid the priest said mass, the first Catholic mass to be held in New Hampshire.4

Although the raid was short lived, an enormous amount of damage was inflicted. Reverend John Pike wrote in his diary: “The Indians fell suddenly and unexpectedly upon Oyster River about break of Day. Took 3 Garrisons (being deserted or not defended) killed and Carried away 94 persons, and burnt 13 houses- this was the fr [first] act of hostility Committed by [them] after ye peace Concluded at Pemmaqd [Pemaquid].”5 It was not uncommon for the Natives who accompanied the French on their raids on New England to take captives, either to be used for ransom or to be raised as replacements for Indians killed in battle.

Mound of earth marking the mass grave near the Mathes Burial ground at Durham Point on the Oyster River and the grave marker placed in 1941

The war ended at the signing of the Treaty of Ryswick in September 1697. Territorial borders returned to where they were pre-war, but many of the people that had been taken hostage over the years did not return; Mercy was one of those.

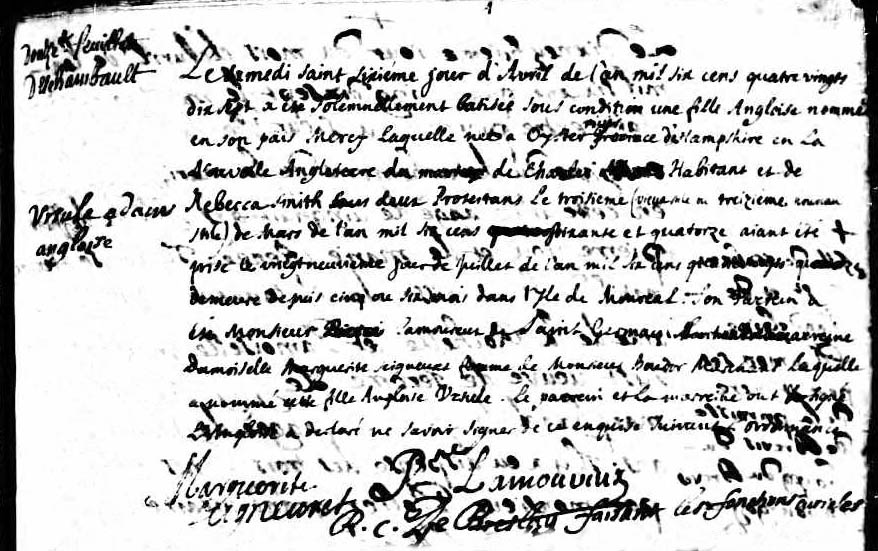

After her kidnapping, Mercy was adopted by Charles Antoine Plagnol, the commandant of the fort at Saint-Francois- du-Lac, and his wife Therese Audrendron (probably a different spelling since I cannot find any record of her). Supposedly Therese had paid the ransom to free Mercy. On April 6, 1697 Mercy was given the Christian name Marie Ursule and baptized into the Catholic faith at the Basilica of Notre Dame at Montreal.

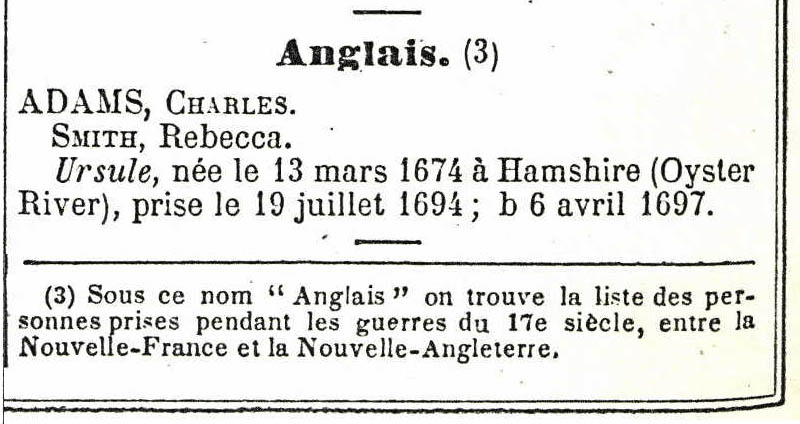

Ursule (Mercy) is first listed in the Genealogical Dictionary of Canadian Families under “Anglaise” instead of a surname. The footnote (3) reads: Under this name “English” we find the list of people taken during the wars of the 17th century, between New France and New England. Even though she is listed using her Christian name, her parents are correctly shown as Charles Adams and Rebecca Smith. The record gives her parents, then her name, date and location of birth, taken July 19, 1694; baptized April 6, 1697.9

Ursule’s future husband Charles Dubois dit Brisebois (my 7th great-grandfather) was born on December 5, 1680 and baptized the same day at Notre-Dame in Quebec City. Charles was the 8th of 9 children born to Anne-Julienne Dumont (a fille du Roi) and Rene Dubois dit Brisebois (my 8th great-grandparents).10 When Charles was born, Anne-Jullienne was 34 years old and Rene was 41 years old.

Translation:

Baptism

Charles du Bois [Dubois]

On the fifth day of December of the year one thousand six hundred and eighty by me J. L. de Brullon pastor of the seminary of Quebec was baptized in the parish church of Notre Dame de Quebec Charles Dubois son of René Dubois and Anne Julienne Dumont his wife residing in Quebec the child was born on the same day, month and year, under the godfather — Charle de Couagne butler of — the governor of Quebec, and his godmother — Geneviève Auber wife of Denis Roberge residing in Quebec and the father declared that he did not know how to write or sign this summons serving as a prescription and which the godfather and godmother had signed.

(Signature of Charle de Couagne)

(Signature of Genevieve Auber) (Signature of J. L. de Brullon, priest)

End of translation.

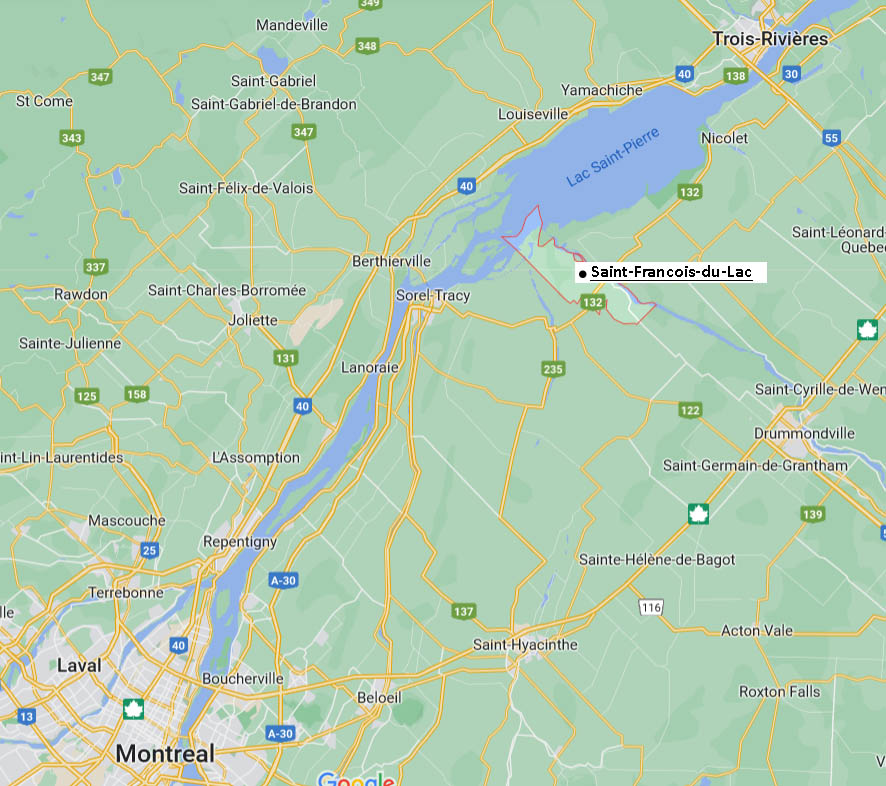

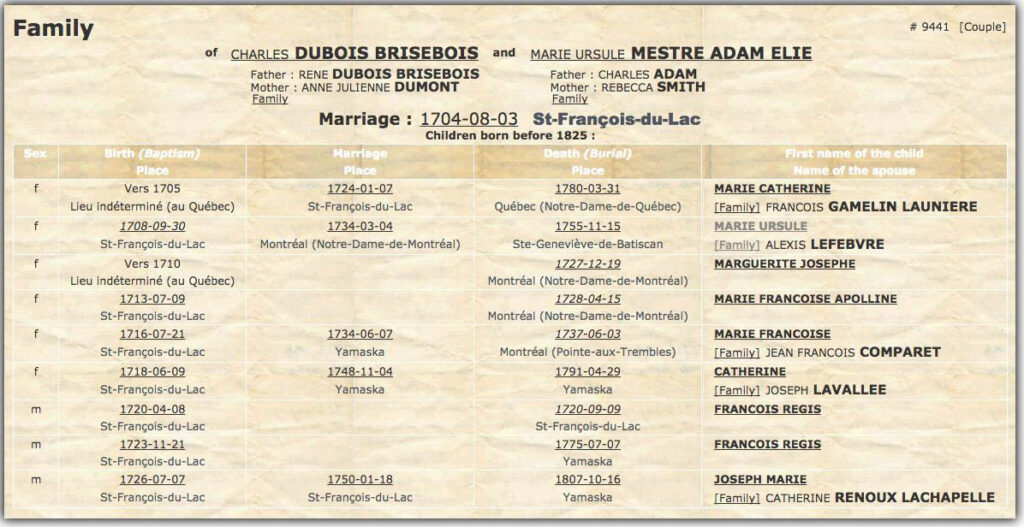

On August 3, 1704 Ursule married Charles Dubois dit Brisebois at Saint-Francois-du-Lac, Nicolet-Yamaska, Quebec, Canada.

Translation:

August 3, 1704

I Jacques Bigot of the Comp. of Jesus exercising the functions of parish priest of St François after the publication of two banns, and dispenses with three years without any impediment to Marie Charle du Bois son of the late Dubois and the late Anne Dumont with Marie Ursule baptized from childhood in this parish and adopted by Monsieur de Plagnol. The witnesses are Claude Pinart, La Bonte, Lozière.

End of translation.

Charles and Ursule made their home in Saint-Francois-du-Lac, Nicolet-Yamaska, Quebec, Canada where over the next 21 years Ursule would give birth to 9 children.

Their 6th child Catherine married Joseph Lavallee. They are my 6th great-grandparents on the Peltier side of the family. However, Joseph’s brother Pierre is also my 6th great-grandfather and the descendants of Pierre are on both the Vadnais and the Peltier sides of the family.

Ursule died at about age 52 on September 15, 1728. She had spent the majority of her life as a Catholic in Canada. I imagine she had memories of her past life, some quite horrifying, but as we all know time fades many memories. I believe she had a good life and that she cherished her family and her children.

On September 29, 1732 Charles, at age 51, married Marie Anne Soucy.15 Both had been widowed and no children were born from this marriage.

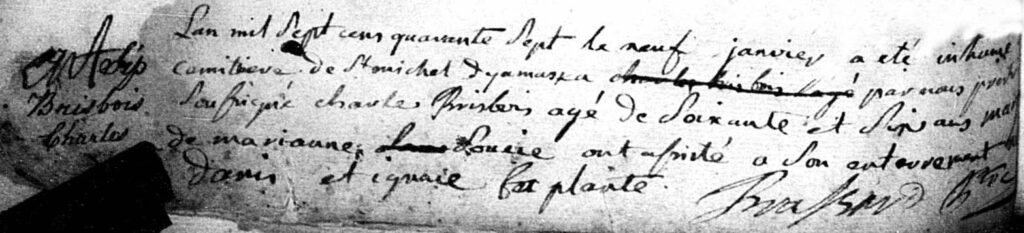

Charles passed away and was buried at Saint-Michel-d’Yamaska, Pierre-De Saurel, Quebec, Canada on Jan 9, 1747 at 66 years old.16 His wife and 4 of his children preceded him in death.

Thanks for visiting, come back soon,

Cindy

© 2022 Copyright by Cynthia Vadnais, All Rights Reserved

Hi, Mercy is also my 7th Great Grandmother, her son Joseph (1726-1807) daughter Catherine married into the Despin’s line… my GG’s. Thanks for sharing this compilation of info!

Kathy